It is likely that, in the not-distant future, wounds will heal faster with the help of an electrical pulse that promotes rapid cell growth. The same type of pulse may be used for more efficient and effective delivery of drugs to fight disease. Such treatments rely on a process known as “electroporation,” in which an electrical field is applied to cells to increase the permeability of the cell membrane. Already, electroporation is being used experimentally to deliver chemotherapy into cancerous cells, but such treatments are in their infancy and involve a great deal of trial and error.

In a new paper that has received widespread attention since being published in the March 1, 2019 Journal of Computational Physics, Professor Frederic Gibou (below left) chair of the Mechanical Engineering Department at the UC Santa Barbara College of Engineering, and a team of UCSB colleagues describe research in which they developed the first computational models to study electroporation at the tissue scale. The research was funded by the U.S. Army Research Office’s (ARO) Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Lab.

ARO mathematical sciences division chief, Joseph Myers, underscores the application of such simulations: "Mathematical research enables us to study the bioelectric effects of cells in order to develop new anti-cancer strategies,” he says. "This new research will enable more accurate and capable virtual experiments of the evolution and treatment of cells — cancerous or healthy — in response to a variety of candidate drugs. Eventually, electric pulsation might also be used to accelerate the healing of combat wounds.”

"This is an exciting but mainly unexplored area that stems from a deeper discussion at the frontier of developmental biology, namely how electricity influences morphogenesis, the biological process that causes an organism to develop its shape,” says Gibou.

Until now, simulations of the effects of electroporation have been conducted on, at most, a few individual cells at a time. But an entire collective system of cells functions much differently than simply the sum of its cellular parts. Not only is it currently not possible to observe the cells as a system in situ, but variables such as environmental temperature and pressure as well as the strength, duration, and pattern of an introduced electrical field affect the behavior not only of individual cells but, more importantly, of the system as a whole.

"When you consider a large number of cells together, the aggregate exhibits novel coherent behaviors,” said Pouria Mistani (below left), a PhD student in Gibou’s group and first author of the paper. “It is this emergent phenomenon — novel behaviors that emerge from the coupling of many individual elements —that is crucial for developing effective theories at the tissue-scale.”

What has been missing to arrive at such a system-scale understanding are the computational algorithms that Gibou’s group created. “There is quite a lot of computational science that goes into the design of algorithms that can consider tens of thousands of well-resolved cells,” Gibou notes. “We devised the parallel algorithms for describing the physics at the cell membranes and then implemented them into a super computer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center. The simulations gave us the data from the summation of the individual cells, and that data gave us access to the emergent phenomenon of the cluster, which we can now mine to develop a theory.”

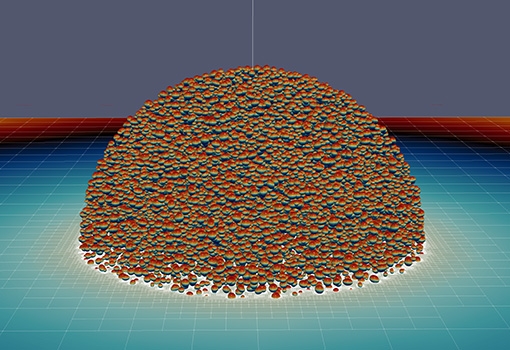

The team began with a phenomenological model for a single cell developed by the research group of Gibou’s longtime colleague, Dr. Clair Poignard, at the Université de Bordeaux, in France. “This model, which describes the evolution of the transmembrane potential on an isolated cell, had been compared and validated with the response of a single cell in experiments,” Gibou says. “We were then able to do a similar simulation for a substantial cluster of cells, applying a large electric field around the entire ball of cells. You can imagine that the cells at the surface are going to get a lot of the current and will shadow what the cells further from the surface get.”

According to Gibou and Mistani, one of the main reasons for the absence of an effective theory at the tissue scale is a lack of data. Specifically, the missing data in the case of electroporation is the time evolution of the transmembrane potential of each individual cell in a tissue environment. Experiments are not able to make those measurements.

"Currently, experimental limitations prevent the development of an effective tissue-level electroporation theory," Mistani said. "Our work has developed a computational approach that can simulate the response of each individual cell in a spheroid comprising tens of thousands of cells to an electric field, as well as the millions of mutual interactions. This has been, by far, the largest simulation of cell aggregate electroporation to date. It has successfully provided terabytes of high-fidelity measurements of electroporation processes on tens of thousands of highly resolved cells in a 3D multicellular spheroid configuration."

"This work could result in an effective theory that helps us to understand the tissue response to these parameters and thus optimize such treatments," Mistani adds. "Previously, the largest existing simulations of cell-aggregate electroporation considered only about one hundred cells in 3D, or were limited to 2D simulations. Those simulations either ignored the real 3D nature of spheroids or considered too few cells for tissue-scale emergent behaviors to manifest."

“Our simulation provides the kind of data you need to build a theory,” Gibou explains. “This is not merely a ‘cheaper way’ to do an experiment. Rather, it delivers information you cannot get from an experiment, because using current experimental techniques, it is not possible to measure the relevant physical features of each and every individual cell. And if you try to perform some measurement by placing an electrode or whatever, you change the entire system.

In their research, Gibou adds, “We mine the data within the framework of statistical physics, a theoretical tool that has been used successfully to describe the simulation results of materials. That allows us to view the cluster as a material and develop the theory. The theory will then give us is a simpler equation for how the cluster behaves and, thus, a tool to understand and control bioelectricity.

“We did the simulation, we are building the framework of the theory to understand the system, and then we’re going to add some complexity to the model to get closer and closer to the behavior of, perhaps, cancer cells,” he adds. “And at the end, when the experiments that can probe average behaviors are performed, they will be more directed because they’re informed by the model.”

This work has received widespread coverage, including on the websites of two national supercomputing facilities — the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) — as well as in several specialized high-performance computing magazines and multiple popular science outlets.

An image from the simulation of a large, spherical cluster of cells responding to an electric pulse. Cells in the aggregate are color-coded by their transmembrane potential (hotter colors on cells imply higher transmembrane potential). The equatorial slice is to illustrate some of the computational techniques used for solving bioelectric interactions on the cell membranes.