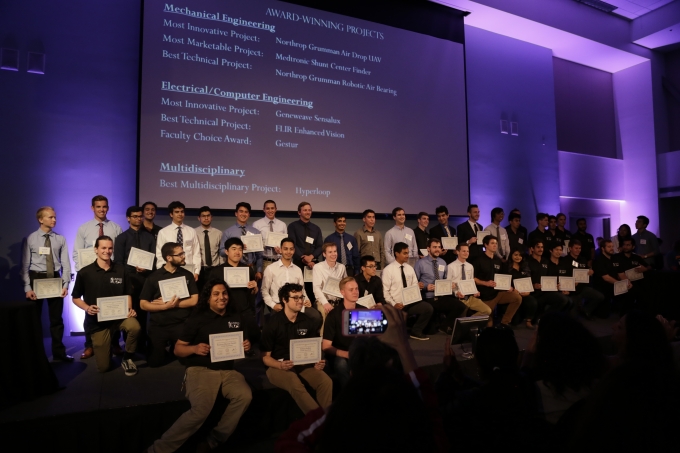

Students from UCSB Mechanical Engineering and Electrical & Computer Engineering impressed the hundreds of people — faculty, sponsors, fellow students, parents, and guests from beyond UCSB — who attended the 2017 UCSB Engineering Design Fair and Showcase, held Friday, June 9, at Corwin Pavilion.

The annual event featured 118 senior undergraduate students, who presented posters and table demonstrations of 21 projects. Three of the projects were large-scale multidisciplinary efforts with 12 to 21 students. Judges walked the fair, talked with the students, and then awarded top honors to the following representatives from each department.

Mechanical Engineering

Most Innovative Project: Northrop Grumman Air Drop UAV

Most Marketable Project: Medtronic Shunt Center Finder

Best Technical Project: Northrop Grumman Robotic Air Bearing

Electrical & Computer Engineering

Most Innovative Project: Genweave Sensalux

Most Marketable Project: FLIR Enhanced Vision

Best Technical Project: Gestur

Multidisciplinary

Best Multidisciplinary Project: UCSB Hyperloop

Explore all of this year's projects on the College of Engineering Capstone page.

“The projects just keep getting better every year,” said UCSB lecturer Ilan Ben-Yaacov, the lead advisor for multiple projects in Electrical and Computer Engineering.

“This year, one-hundred percent of our sponsors were happy,” added Tyler Susko, UCSB lecturer, who manages the Capstone program in Mechanical Engineering. “Our students are all smart and capable, but ambition and inner drive are what make a good project, and these students had it.”

The students themselves shared a number of takeaways from their projects beyond creating technology.

“This project was electrical engineering oriented, and we had to learn a lot from scratch,” said Zachary Levaton, referring to the Medtronic Center Finder for Shunt Valve Project. “It was very iterative, and we failed a lot. We took steps forward and made something that might work, and then failed again. It was never a straight trajectory.”

The dynamics on a 13-person team are so different than for any other project I’ve ever worked on,” said Madeline Dippel, part of the Sonos COM Project. “Working with so many people in so many disciplines, you have to develop communication skills, which are incredibly useful, even if it’s not easy. It took us a whole quarter to be able to communicate effectively.”

“We got to directly impact someone,” said Alison Poffenroth, who worked on the Cadence–sponsored Assistive Shoe for Foot Drop Project. “We had someone who had dropfoot [a neurogical condition affecting some 8 million Americans] and could actually test the shoe, and she felt a difference. Her response was, ‘This is the shoe I’ve been waiting for,’ so it was really rewarding for us.”

“One of the most difficult things about our project was that it was very open-ended,” said Jake Carrade, one of four members of the Advanced Imaging Drone Project, sponsored by the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. “They said what they wanted but didn’t tell us what sensors they wanted or how to go about making the project a reality. It took almost a full quarter to select the components, so it looked like we hadn’t really accomplished anything — it’s easy to overlook how much goes into that aspect of the project.”

“Learning to make a schedule and hit deadlines, the whole project management. Starting something and carrying it out for a whole year — that really prepared me well for working in industry,” said Cole Myhre, who worked on the Northrop Grumman Shock Project.

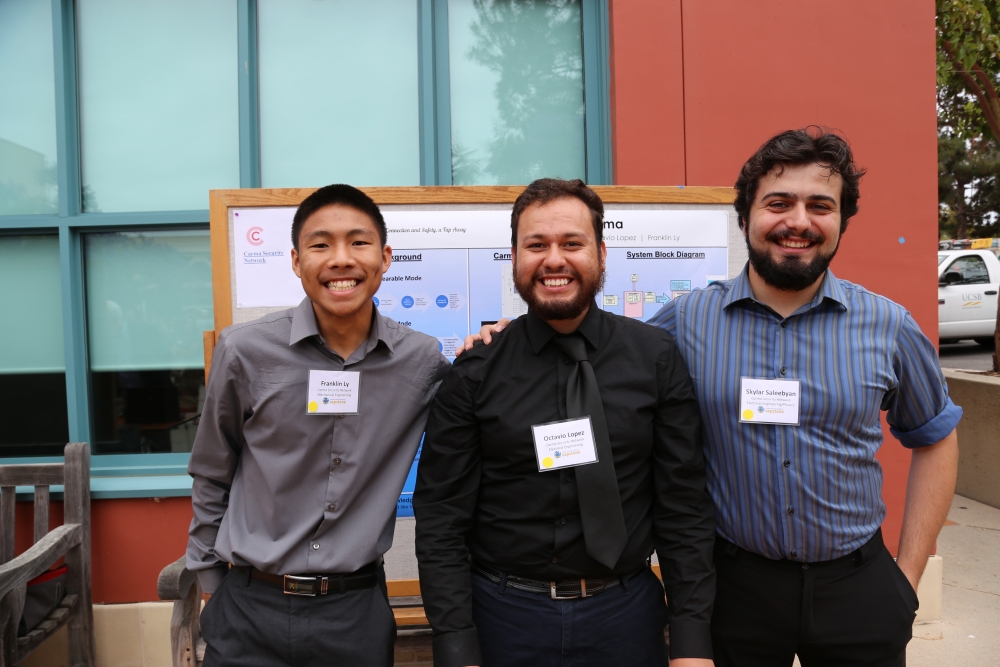

“We started with a 360-degree dash-cam device,” said Franklin Ly, one of three highly adaptable members of the Carma Security Network Project. “We did market research on what people wanted and ended up pivoting our idea to a more wearable type of device that has some modular capability. Now, after more research, we want to deviate from even using a device and more to using just your app and your phone and what’s already there. It’s expensive for a startup to build hardware. Because we kept pivoting, we would come up with something and work on it and then had to scrap it. It was a bummer but also a really good experience for us since we’re actually trying to become a startup.”

Ben May, of the FLIR Helios Project said, “There was a lot of trial and error. One thing I learned is that your first try is never going to be perfect so don’t try to make it be.”

One of the biggest takeaways was definitely learning how to work with a big team on a massive project,” said Forest Wanket, a member of the 21-student UCSB Hyperloop Project, which continued the work begun by another group last year. “That’s probably going to be one of the most critical skills entering the engineering field — being able to communicate with everyone, listening to their ideas, and being able to have people tell you no.”

Proud students receive their certificates of completion of the capstone program.