Classical computing is built upon the power of the bit, which is, in essence, a micro transistor on a chip that can either be on or off, representing a 1 or a 0 in binary code. The quantum computing equivalent is the qubit. Unlike bits, qubits can be in more than one “state” at a time, enabling quantum computers to perform computational functions exponentially faster than classical computers can.

To date, most efforts to build quantum computers have relied on qubits created in superconducting wires chilled to near absolute zero or trapped ions held in place by lasers. But those approaches face certain challenges, most notably that the qubits are highly sensitive to environmental factors. As the number of qubits increases, those factors are more likely to compound and interrupt the entanglement of qubits required for a quantum computer to work.

Another approach that has been developed more recently is to use a photon as an optical qubit to encode quantum information and to integrate the components necessary for that process onto a photonic integrated circuit (PIC). Recently, Galan Moody, an assistant professor in the UC Santa Barbara College of Engineering’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE), received a Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP) Award from the U.S. Department of Defense and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research to build a quantum photonic computing testbed. He will conduct his research in a lab set aside for such activity in recently completed Henley Hall, the new home of the CoE’s Institute for Energy Efficiency.

The grant supports the development or acquisition of new instrumentation to be used in fundamental and applied research across all areas of science and engineering. “My field is quantum photonics, so we’re working to develop new types of quantum light sources and ways to manipulate and detect quantum states of light for use in such applications as quantum photonic computing and quantum communications,” Moody said.

“At a high level,” he explained, the concept of quantum photonic computing is “exactly the same as what Google is doing with superconducting qubits or what other companies are doing with trapped ions. There are a lot of different platforms for computing, and one of them is to use photonic integrated circuits to generate entangled photons, entanglement being the foundation for many different quantum applications.”

To place an entire quantum photonics system onto a chip measuring about one square centimeter would be a tremendous achievement. Fortunately, the well-developed photonics infrastructure — including AIM Photonics, which has a center at UCSB led by ECE professor and photonics pioneer John Bowers — lends itself to that pursuit and to scaling up whatever quantum photonics platform is most promising. Photonics for classical applications is a mature technology industry that, Moody said, “has basically mastered large-scale and wafer-scale fabrication of devices.” It is reliable, so whatever Moody and his team design, they can fabricate themselves or even order from foundries, knowing that they will get exactly what they want.

The Photonic Edge

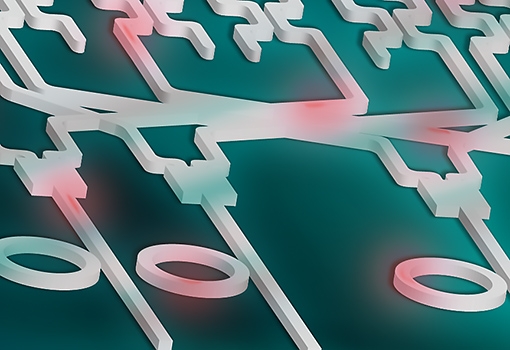

The process of creating photonic qubits begins with generating high-quality single photons or pairs of entangled photons. A qubit can then be defined in several different ways, most often in the photon’s polarization (the orientation of the optical wave) or in the path that the photons travel. Moody and his team can create PICs that control these aspects of the photons, which become the carriers of quantum information and can be manipulated to perform logic operations.

The approach has several advantages over other methods of creating qubits. For instance, the aforementioned environmental effects that can cause qubits to lose their coherence do not affect coherence in photons, which, Moody says, “can maintain that entanglement for a very long time. The challenge is not coherence but, rather, getting the photons to become entangled in the first place.”

“That,” Moody notes, “is because photons don’t naturally interact; rather, they pass right through each other and go their separate ways. But they have to interact in some way to create an entangled state. We’re working on how to create PIC-based quantum light sources that produce high-quality photons as efficiently as possible and then how to get all the photons to interact in a way that allows us to build a scalable quantum processor or new devices for long-distance quantum communications.”

Quantum computers are super-efficient, and the photonics approach to quantum technologies is even more so. When Google “demonstrated quantum supremacy” in fall 2019 using the quantum computer built in its Goleta laboratory under the leadership of UCSB physics professor John Martinis, the company claimed that its machine, named Sycamore, could do a series of test calculations in two hundred seconds that a super-computer would need closer to ten thousand years to complete. Recently, a Chinese team using a laboratory-scale table-top experiment claimed that, with a photon-based quantum processor, “You could do in two hundred seconds what would take a super-computer 2.5 billion years to accomplish,” Moody said.

Another advantage is that photonics is naturally scalable to thousands and, eventually, millions of components, which can be done by leveraging the wafer-scale fabrication technologies developed for classical photonics. Today, the most advanced PICs comprise nearly five thousand components and could be expanded by a factor of two or four with existing fabrication technologies, which is at a comparable stage of development that digital electronics were in the 1960s and 1970s. “Even a few hundred components is enough to perform important quantum computing operations with light, at least on a small scale between a few qubits,” says Moody. With further development, quantum photonic chips can be scaled to tens or hundreds of qubits using the existing photonics infrastructure.

Moody’s team is developing a new materials platform, based on gallium arsenide and silicon dioxide, to generate single and entangled photons, and it promises to be much more efficient than comparable systems. In fact, they have a forthcoming paper showing that their new quantum light source is nearly a thousand times more efficient than any other on-chip light source.

In terms of the process, Moody says, “At the macro level, we work on making better light sources and integrating many of them onto a chip. Then, we combine these with on-chip programmable processors, analogous to electronic transistors used for classical logic operations, and with arrays of single-photon detectors to try to implement quantum logic operations with photons as efficiently as possible.”

For more accessible applications, like communications, no computing needs to occur. “It involves taking a great light source and manipulating a property of the photon states (such as polarization), then sending those off to some other chip that’s up in a satellite or in some other part of the world, which can measure the photons and send a signal back that you can collect,” Moody said.

One catch for now is that the single-photon detectors, which are used to signal whether the logic operations were performed, work with very high efficiency when they are on the chip; however, some of them work only if the chip is cooled to cryogenic temperatures. “If we want to integrate everything on chip and put detectors on chip as well, then we’re going to need to cool the whole thing down,” Moody said. “The DURIP award enables us to design the instrumentation we need to test large-scale quantum photonic chips from cryogenic temperatures all the way up to room temperature."

Concept illustration depicting an integrated photonic quantum processor: Laser light coupled into the channels interacts with the rings (foreground) to create pairs of entangled photons (red). The entangled photons split and travel throughout the photonic circuit (background), which controls effective interactions between them, enabling optical quantum computations. Illustration by Lillian McKinney