You’ve seen people sliding into the tube of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine on your favorite medical drama, or maybe you’ve been inside one yourself, waiting as the noisy scanner makes images of your brain, heart, bones, or other structures, which doctors use to identify injury or disease.

Since the 1970s, MRIs have been important diagnostic tools, combining a magnetic field and radio waves to produce snapshots of the body’s interior without using ionizing radiation, which can create health risks at higher doses. An MRI can typically capture changes in anatomy, but the molecular-level changes that could further aid understanding of disease have been beyond its reach.

“You can see the structures of your tissues — whether it's the brain, the heart, the kidneys or the stomach — but you don't get molecular information,” says Arnab Mukherjee, an associate professor of chemical engineering at the UC Santa Barbara Robert Mehrabian College of Engineering. “So, the only time you can know that something is going wrong or something has changed is if you take another MRI, and the structure and morphology of the tissue changes.” For many diseases and conditions, he adds, by the time the structure has changed, the disease has progressed.

Ever since he was a postdoctoral researcher at California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Mukherjee has been looking for ways to improve the usefulness of MRIs for identifying real-time changes at the molecular level to aid basic science and animal studies, which may have future applications for human health. “If we can see these molecular-level changes happening in real time, then we can ask questions like, How do tumor cells metastasize or how does neurodegeneration progress at the molecular level as an animal ages?” he says. “There's currently no way to do that.”

A Sensor-based Approach

Mukherjee and his colleagues are applying concepts related to synthetic biology to catch structural and molecular changes “in the act.” To that end, they have created a protein-based sensor that can be genetically engineered into cells, allowing an MRI to visualize molecular processes. The technique could increase understanding of neurodegenerative diseases, cancer development, inflammation, and other irregularities that cause changes in health. The sensor that the team has developed is modular, allowing researchers to attach or substitute specific proteins to target different processes within cells. An article published in January in the journal Science Advances outlines the sensor and its LEGO-like architecture.

In order to give the MRI the power to see such fine-grained changes in cells, Mukherjee and his team had to find a sensor that the MRI would be able to “see” inside cells, tissues, and other structures. An MRI works by creating a magnetic field, which aligns most of the hydrogen atoms in the structure being scanned. Radio waves then use the remaining hydrogen atoms to create an image. It’s a powerful way to peer inside the body, but it cannot be used to obtain molecular level information.

Since the 1960s, researchers have been using genes found in jellyfish-derived fluorescent proteins to tag proteins, genes, and individual molecules in a cell and then watch what unfolds under a fluorescence microscope. These glowing proteins have allowed scientists to watch processes such as an immune cells’ response to a pathogen or the growth of tumor cells in real time.

At Caltech, Mukherjee began looking for proteins that would allow an MRI to do something similar, that is, giving off a “glow” that could be picked up in the magnetic field and then imaged. This molecular precision would give researchers and, someday, health-care providers, the ability to track the progress of neurodegeneration in the brain or to see whether a particular drug is successfully keeping cancer cells at bay.

His work led him to aquaporin, a protein that forms an hourglass-shaped channel in the cell membrane, allowing water to move in and out of the cell. “Our water molecules are tiny, tiny magnets,” Mukherjee says. “If you can control or affect the rate at which water molecules move back and forth across the cell, you can make that magnetic signal specific to certain types of cells or biological processes, which would allow the MRI to report on this process at the molecular level, thus providing much more detailed information than are currently possible.”

Once Mukherjee arrived at UCSB, in 2017, he started working to make this approach useful for visualizing a variety of cellular targets and processes. He and his colleagues began combining aquaporin with different proteins to make genetic “circuits” that can be tailored to what a researcher is studying. Asish Ninan Chacko (PhD ’26), then a chemistry and biochemistry PhD student in Mukherjee’s lab, worked to fine-tune the system. “This protein can be regulated using a lot of chemical signals,” which can be added like building blocks to the sensor, says Chacko. “We can even replace this particular protease with another type of protease, and use it to detect many different processes.”

Building Blocks

The interchangeable system, called MAPPER (for modular aquaporin-based protease-activatable probes for enhanced reporting), makes it possible to use aquaporin-driven MRI to track a number of chemical processes inside cells in a laboratory setting. “That’s a first in this paper,” Chacko says, “because, so far in the scientific literature, you’ve seen only four or five genetic sensors, each used to detect a unique analyte,” or the chemical or compound being measured. “In this paper, we describe close to ten systems we can detect with this one setup.”

The researchers envision their tool being used to improve the reliability of animal studies in disease progression, while reducing the demand on lab animals. “Right now, if you need to access an animal’s internal organs as part of a study, there is no way to do it without sacrificing the animal. And you’re limiting your experiment to a single snapshot in time — which can be misleading because animals vary in their metabolism and response to treatment,” Chacko says. “Our approach allows continuous imaging of the same animal over the course of a study, giving a far more accurate picture of disease and of biology.”

Because of the building-block nature of the system, that is, the ability to stack aquaporin with a custom array of proteins to visualize different processes, researchers would not need to design a new MRI sensor from scratch each time they wanted to monitor a new chemical or process. Instead, they could add different components to the MAPPER system — enabling them to develop a sensor within a few months, says Mukherjee, who envisions creating a summer training program for undergraduates to learn the process.

“We want to take these sensors and put them in the hands of people who will actually use them,” he says, “whether that’s neuroscientists, who would be able to use MAPPER to look at calcium changes in the brain, or developmental biologists, who could use the tools to track mouse development from embryo to adult.”

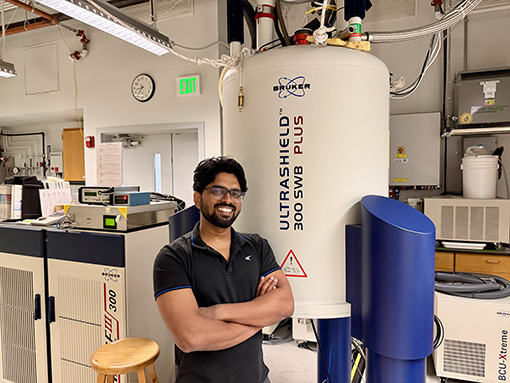

Study lead author Asish Ninan Chacko (PhD '26) used the Materials Research Laboratory's MRI machine to develop a new sensor for understanding disease at the molecular level.