CELEBRATING WOMEN'S HISTORY MONTH

In honor of National Women’s History month, which is celebrated for the entire month of March, the College of Engineering (COE) would like to honor the following group of impressive female and female-identifying engineers. The collection below includes pioneering women who made tremendous contributions in the past and others who continue to make them today, including the 31 remarkable women who are faculty members in the COE. We honor these women for their tenacity and determination, and for the unique perspectives they bring to the field. Their work has changed the world.

FEMALE FACULTY IN UCSB’S COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING

Mahnoosh Alizadeh

Associate Professor

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Elizabeth Belding

Professor, Associate Dean

Computer Science

Irene Beyerlein

Professor

Materials, Mechanical Engineering

Katie Byl

Associate Professor

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Raphaële Clément

Assistant Professor

Materials

Yufei Ding

Assistant Professor

Computer Science

Adele Doyle

Assistant Professor

Mechanical Engineering

Emilie Dressaire

Assistant Professor

Mechanical Engineering

Songi Han

Professor

Chemical Engineering

Yekaterina Kharitonova

Assistant Teaching Professor

Computer Science

Chandra Krintz

Professor

Computer Science

Kyle Lewis

Professor and Chair

Technology Management

Nina Miolane

Assistant Professor

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Diba Mirza

Associate Teaching Professor

Computer Science

Yasamin Mostafi

Professor

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Michelle O’Malley

Professor

Chemical Engineering

Sumita Pennathur

Professor

Mechanical Engineering

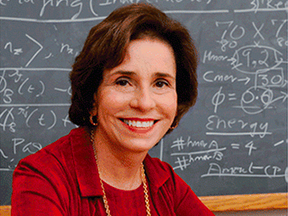

Linda Petzold

Professor

Mechanical Engineering, Computer Science

Angela Pitenis

Assistant Professor

Materials

Tresa Pollock

Interim Dean and Professor

Materials

Beth Pruitt

Professor

Mechanical Engineering

Renee Rottner

Assistant Teaching Professor

Technology Management

Jessica Santana

Assistant Professor

Technology Management

Susannah Scott

Professor

Chemical Engineering

Rachel Segalman

Professor and Chair

Chemical Engineering, Materials

Misha Sra

Assistant Professor

Computer Science

Susanne Stemmer

Professor

Materials

Mary Tripsas

Professor

Technology Management

Megan Valentine

Professor

Mechanical Engineering

Yangying Zhu

Assistant Professor

Mechanical Engineering

PIONEERING WOMEN OF ENGINEERING

Chemical Engineering

Carol K. Hall

Raised in Brooklyn, Carol K. Hall majored in physics at Cornell University, because, she says, “My physics teacher told my mother, ‘Girls can be physicists too.’” She earned her PhD at New York’s Stony Brook University and worked at Bell Labs before becoming an assistant professor in Princeton University’s Chemical Engineering Department, making her the first female tenure-track professor in the department and only the third female chemical engineering faculty member in the nation. But sexism was rampant. One male professor told her, “Everyone knows women can't do science,” and the senior faculty denied Hall tenure. She eventually relocated to North Carolina State University, where, in the late 1990s, she turned her attention to the proteins that are involved in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including those that affected her parents. She was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering "for applications of modern thermodynamic and computer-simulation methods to chemical engineering problems involving macromolecules and complex fluids." She became a fellow of the American Physical Society in 2007, being cited for “creating a new paradigm to simulate protein aggregation through a combination of intermediate-resolution molecular models and the discontinuous molecular dynamics method.” She is also a fellow of the American Institute of Chemical Engineers and, in 2019, was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Paula Hammond

Growing up in a Detroit neighborhood populated by many Black professionals, and with a mother who was a nurse and a father who was a biochemist, Paula Hammond gravitated naturally to science. She attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she was excited by the intellectual power but recalls experiencing impostor syndrome as one of few Black women in a field then dominated by White men. With the support of the Black Student Union, she completed her degree, then went to work for Motorola before earning her MS and PhD at the Georgia Institute of Technology, where she developed an enduring love for polymer research and its application in electrochemical and optical devices. After a stint as a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University, she returned to MIT as an assistant professor, where she began conducting research on how to manipulate cells to deliver anti-cancer drugs. She formed a multidisciplinary group of MIT faculty that ultimately became the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, working on materials for protective clothing made from high-strength fibers and developing materials that could rapidly stop bleeding on the battlefield. She and a colleague eventually co-founded LayerBio, focusing on ophthalmologic applications for polymers. President Obama visited Hammond’s lab in 2009, and Hammond now serves as department chair of MIT’s Chemical Engineering Department.

Materials

Julia Weertman

Enthralled with airplanes as a young girl, Julia Weertman, who died in 2018 at the age of 92, was the first female student of the College of Science and Engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where she earned her baccalaureate and graduate degrees. As a faculty member at Northwestern University, Weertman became known for her research on high-strength, high-temperature alloys and nanocrystalline metals. She spent six years working on magnetism at the U.S. Naval Research Lab. In 1987, she was appointed chair of Northwestern's Department of Materials Science and Engineering, becoming the first woman in the United States to lead a materials science department. She was granted membership in the National Academy of Engineering in 1988, earning recognition for “exceptional research on failure mechanisms in high-temperature alloys." In 1989, she became the first female fellow of The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society, and the first female member of its Board of Directors. Having paused her career to raise a family, Weertman wrote that her toughest challenge was “re-entering the work force after thirteen years of parenting, switching fields of expertise, and starting up a research program with encouragement but no start-up funds or equipment.”

Carolyn Hansson

Canadian materials engineer Carolyn Hansson is known for her research on the corrosion of steel inside reinforced concrete, and for having pioneered a monitoring system to evaluate the integrity of concrete structures, and for identifying techniques to measure the amount of corrosion. She has worked in corrosion monitoring of bridge structures while serving as a consultant to the Ministry of Transportation Ontario and Alberta Transportation and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada for her contributions in the basic science of corrosion and metallurgical processes and applied engineering. Raised in England, she was the first female student to attend the Royal School of Mines at Imperial College, London, and the first woman to graduate from it with a PhD in metallurgy, making her, at the time, one of only two women in the United Kingdom with a PhD in metallurgy. In 1976, Hansson joined AT&T Bell Labs and stayed for four years before spending the following nine as a research scientist, and eventually as head of the Research Department, at the Danish Corrosion Centre. Hanson and her husband moved to Maryland, where she accepted an appointment within Martin Marietta’s Institute for Advanced Studies. In 1990, she became a professor and head of the Materials and Metallurgical Engineering Department at Queen's University and in 1996 was named Vice President of University Research at the University of Waterloo. The following year, she was elected a Fellow of The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society.

Bioengineering

Linda Gay Griffith

Linda Gay Griffith is a professor of biological engineering and mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Growing up near the Okefenokee Swamp in southern Georgia, she studied chemical engineering at Georgia Tech and earned her PhD in biotechnology at UC Berkeley. Her research encompasses molecular-to-systems level analysis, design and synthesis of biomaterials, scaffolds, devices and micro-organs for a range of applications in regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, and in vitro drug development. In the prelude to an MIT interview, she was described as “shaping the frontiers of tissue engineering and synthetic regenerative technologies through cutting-edge research at the intersection of materials science, cell surface chemistry, physiology, and anatomy.” A former MacArthur Fellow, she began sewing at a young age and says, “This idea of designing and being quantitative…has permeated. I've always liked making things. When I'm 12, I'm knitting, and when I'm 30, I'm building molecules that are used in regenerative medicine. I am an engineer who builds things. I build things mainly out of molecules. I build things out of biology. But that intrinsic process of defining something you want to build that has a purpose and going all the way back to first principles to the tools you have to build it and going through some kind of model, design, blueprint process — that's engineering.”

Viola Vogel

Viola Vogel is a German biophysicist and bioengineer and a professor at ETH Zürich, where she is head of the Department of Health Sciences and Technology and leads the Applied Mechanobiology Laboratory. In 1988 she won an Otto Hahn Medal for her doctoral work with Hans Kuhn at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, in Göttingen. In 1990, after two years as a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Physics at UC Berkeley, she took a faculty position in the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Washington, Seattle, where she initiated the molecular bioengineering program. She was subsequently founding director of the Center for Nanotechnology there, serving in that role from 1997-2003. In 2004 she relocated to ETH Zürich, first as a professor in the Department of Material Sciences, and later as a founding member of the Department of Health Sciences and Technology. The direction of Vogel's work is to investigate the mechanical properties of living tissues, with a view to developing new technologies. Her interests include molecular self-assembly, cell adhesion, and the construction of biological minerals, materials, and tissues. Her experimental and computational discoveries of how stretching proteins changes their function, and how cells sense and respond to force, have applications in stem cell differentiation, tissue growth and regeneration, angiogenesis, and cancer.

Electrical and computer engineering

Ellen Ochoa

Ellen Ochoa is an American engineer and a former astronaut who in 2012 was named director of the Johnson Space Center, in Houston, becoming the center’s first Hispanic director and the second female director. In 1993, Ochoa became the first Hispanic woman to go to space, when she served on a nine-day mission aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery, which had the mission of studying Earth’s ozone layer. She would travel to space three more times on Space Shuttle missions, and was among the first in Mission Control to learn of the fate of the Space Shuttle Columbia. Ochoa’s grandparents immigrated from Mexico, and Ochoa was one of five children. A first-generation college student, she received her BS in physics from San Diego State University, then went earned her MS and PhD in the Stanford University Department of Electrical Engineering. At Stanford, and later as a researcher at Sandia National Laboratories and the NASA Ames Research Center, Ochoa investigated optical systems for performing information processing. She patented a system to detect defects in a repeating pattern and is a co-inventor on three patents for an optical inspection system, an optical object recognition method, and a method for removing “noise” from images. She currently chairs the committee that evaluates nominations for the National Medal of Technology and Innovation.

Mildred Dresselhaus

Growing up in the Bronx during the Great Depression, Mildred Dresselhaus credited her early interest in science to the trips she used to make to Manhattan’s free public museums. The woman who would become known as the "Queen of Carbon Science” died in 2017 at the age of 86 after a 57-year career as a professor of physics and electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, during which she became the first woman to be named an Institute Professor. Dresselhaus was particularly noted for her work on graphite, graphite intercalation compounds, fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, and low-dimensional thermoelectrics. Her research helped develop technology based on thin graphite, allowing electronics to be everywhere, including on clothing and in smartphones. Dresselhaus won bushels of awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor bestowed by the U.S. government, the National Medal of Science, the Enrico Fermi Award, the Vannevar Bush Award, and the Kavli Prize, for her “pioneering contributions to the study of phonons, electron-phonon interactions, and thermal transport in nanostructures.” In 1990 she received the National Medal of Science in recognition of her work on the electronic properties of materials, as well as for expanding the opportunities of women in science and engineering. She was inducted into the U.S. National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014 and the following year was awarded the IEEE Medal of Honor. During her career, she directed the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, served as chair of the governing board of the American Institute of Physics, was president of the American Physical Society, and became the first female president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Dedicated to expanding the presence of women in science, in 1971 Dresselhaus and a colleague organized the first Women's Forum at MIT, to explore the roles of women in science and engineering.

Computer Science

Grace Brewster Murray Hopper

A computer pioneer and naval officer, Grace Brewster Murray Hopper is celebrated for her trailblazing contributions to the development of computer languages. She graduated from Vassar College in 1928, with degrees in mathematics and physics and went on to receive a master’s degree in 1930 and a PhD in 1934, both in mathematics from Yale. Hopper was the first to devise the theory of machine-independent programming languages, and the FLOW-MATIC language she created was the first to use English-like commands. It was later extended to create COBOL, which is still in use today. She worked with computer pioneer Howard H. Aiken to develop the Mark I computer, and later the Mark II and Mark III computers. Once, when the Mark II malfunctioned, she and her colleagues took the machine apart and found a large moth. From that experience, Hopper originated the phrase to “debug” a computer. As a Navy Reserve officer during World War II, Hopper and her fellow officers worked in a Harvard lab, performing top-secret calculations for the war effort. Forced into age-restricted retirement in 1966, Hopper was recalled to active service as the Vietnam War heated up. She remained on active duty for 19 years. retiring as a rear admiral at 79, as the oldest serving officer in the U.S. Armed Forces. In 1991 President George H. W. Bush awarded Hopper the National Medal of Technology, making her the first woman to receive the nation’s highest technology award. She died in 1992 and was awarded, posthumously, the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016. Every year, the AnitaB.org hosts its Grace Hopper Celebration, which attracts some 20,000 attendees per year, who come to honor Hopper’s legacy and promote the inclusion and achievements of intersectional women technologists.

Ada Lovelace

The daughter of mathematician Annabella Milbanke Byron and famed poet Lord Byron, who left her mother shortly after her birth, Ada Lovelace was educated privately by tutors. Arround 1837, English mathematician Charles Babbage built a part of what he called the Analytical Engine. Lovelace was the first to recognize that the unfinished machine had applications beyond pure calculation, and she published the first algorithm intended to be carried out by such a machine. As a result, she is often regarded as the first computer programmer. The early programming language "Ada" was named for her, and in England, the second Tuesday in October is Ada Lovelace Day, on which the contributions of women to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics are honored. Ada described her approach as "poetical science" and herself as an "Analyst (& Metaphysician)." Between 1842 and 1843, Lovelace translated an article by Italian military engineer Luigi Menabrea about the Analytical Engine, supplementing it with an elaborate set of notes, which amount to an early history of computers and contain what many consider to be the first computer program—that is, an algorithm designed to be carried out by a machine. Her mindset, self-described as "poetical science," led her to ask questions about the Analytical Engine, which amounted to examining how individuals and society relate to technology as a collaborative tool.

Mechanical Engineering

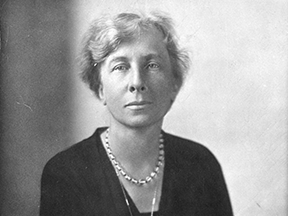

Lillian Evelyn Gilbreth

In an era before specialization, Lillian Evelyn Gilbreth, who lived from 1878-1972, was an American psychologist, industrial engineer, consultant, and educator, as well as early pioneer in applying psychology to time-and-motion studies. As one of the first female engineers to earn a PhD, she is considered the first industrial/organizational psychologist. She and her husband, Frank Bunker Gilbreth, were efficiency experts and equal partners in a consultancy that promoted their research findings. For more than forty years, Gilbreth helped industrial engineers recognize the importance of the psychological dimensions of work, becoming the first American engineer to create a synthesis of psychology and scientific management. Together, the Gilbreths were the first to document work processes on film in order to redesign machinery to better suit workers' movements and, thus, improve efficiency and reduce fatigue. Because of discrimination in the engineering community, Lillian Gilbreth shifted her efforts toward research projects in the female-friendly arena of domestic management and home economics, where she "sought to provide women with shorter, simpler, and easier ways of doing housework to enable them to seek paid employment outside the home." She was also instrumental in the development of the modern kitchen, creating the "work triangle" and linear-kitchen layouts that are often used today.

Yvonne Clark

An intersectional pioneer as an African American female engineer, Yvonne Clark was the first woman to receive a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering at Howard University (1951), the first woman to earn a master's degree in Engineering Management from Vanderbilt University, and the first woman to serve as a faculty member in the College of Engineering and Technology at Tennessee State University, where she made great efforts to encourage women to become engineers, reporting in 1997 that 25 percent of the students in her department were female. Raised by her mother, a librarian and a journalist, and her father, a physician and a surgeon, Clark was always building and repairing things as a child. But girls were not allowed to take mechanical drawing class at her school, so she took an aeronautics class including flight lessons in a simulator. Finding that "the engineering job market wasn't very receptive to women, particularly women of color” after graduating from Howard, she earned her master’s degree and then worked at an ammunition plant before designing factory equipment at a record plant in New Jersey. In her varied career, she did research on recoilless weapons and worked for NASA investigating Saturn V engines for hot spots and helping design the containers Neil Armstrong used to bring Moon samples back to earth. She also discovered methods for revitalizing and modernizing part of the inner city in Baltimore. Clark died in 2019.

STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS AND ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Society of Women Engineers, UCSB Chapter

Women in Science and Engineering, UC Santa Barbara

UCSB Women in Computer Science

Women’s History Month Through the Scope of SWE

COE Salutes Impactful Black Engineers (Published in February 2022)